The Attack of the Cottontails

16th July 1807. The Treaties of Tilsit between the Franco-Russian Empire had concluded just a few days ago. The power of Napoleon was at its peak. Set on the plains of modern-day Poland, one could easily make out his tent from a distance: an extraordinary 18th-century tapestry and gilt embroidered work, crafted by the Gobelins in Paris. The patch of evening sunlight wrapped it in a golden hue. Inside, Bonaparte was reclining on his canopy cot with emerald-green screens tied on both sides. His eyes were carefully scanning the intricate works of his tepee. He gave a thought, “it’s time for a celebration.” Napoleon stood up from his plush wooden bed and asked for his Military Chief Louis Alexandre Berthier.

“What kind of ceremony do you think will fit this moment of triumph?” Napoleon asked.

The French Monarch didn’t wait for his deputy’s answer.

He quickly proposed an idea: “Organise a hunting feast. Wild hares are what I would like to hunt with my men.”

Napoleon Bonaparte’s extreme love for hunting wasn’t a secret among his men. His predecessors—the House of Bourbons—were fond of hunting, too, especially Louis XIV. It played an important part in their Monarchial tendencies, along with over-the-top splurge in their courts and in wars.

Louis Alexandre Berthier was a man of extraordinary character: a skilled operational organizer and one of the key persons behind Bonaparte’s massive success. He was one of those few soldiers of his times who took part in the American Revolutionary Wars, the French Revolutionary Wars, and the Napoleonic Wars. But that day, he was a little absent-minded.

Alexandre commanded the capture of some 3000 tamed rabbits and put them inside a cage. The idea was to impress Bonaparte with a high kill-rate since domesticated bunnies were easier for target playing. On the day of hunting, they would open the cage doors. Everything was minutely planned, except it didn’t go as they would have liked it.

When Napoleon and his military pooh-bahs arrived at the scene and ordered the start of the hunting, the cage doors were flung open. They thought the ‘wild hares’ would scramble and run for their life. But they didn’t. The conies came out of their cages and stared right in the eyes at the assemblage of Europe’s most powerful men. Napoleon and his camarades found it amusing. With guns still in their leather holster, they started laughing at what was unfolding in front of them. But soon their entertainment turned into horror.

The furry cottontails waged an unspoken ‘war.’ They went straight for the Emperor. It horrified everyone, including Alexandre Berthier. They started fending them off with whatever they could find—muskets, rifles, sabers, horse reins, and even flag posts. But the numbers were still pouring in. The mighty Franco Army, for once, now was supremely outnumbered by these long-eared species. All pandemonium broke loose in the field. Screams of anarchy filled the air with fear and discontentment. Reinforcements stationed at a distance quickly buckled up and rushed for the spot. They saw bunnies leaping on the jackets, trousers, and military backpacks of the bigwigs.

Napoleon Bonaparte ordered a hasty retreat from the place. It took a champion of a coach driver to save the Monarch from the ferocity. He removed a few rabbits from his coach, too. Words of this humiliation soon occupied every conversation—among locals, noblemen, army, and his closest members. It rose like dust plumes and dispersed in thin air. The incident became an embarrassment that haunted Bonaparte, who once compared himself with Alexander the Great, for the rest of his life, or at least until his ultimate defeat in the Battle of Waterloo.

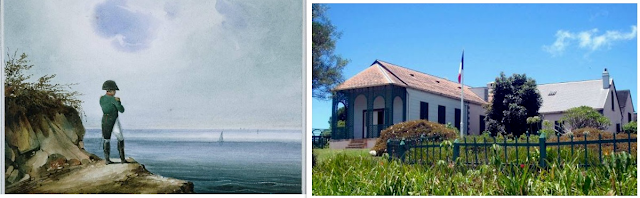

St. Helena, an island in the middle of nowhere:

Among a handful of servants, a lonely man—stripped of his country, his men, his court, and his title—Napoleon Bonaparte glanced at the infinity in front of him. The thoughts of his embarrassing retreat that day and his misjudgment of the English in Waterloo slowly pushed him to the brink of a painful death.

What actually happened:

The tamed rabbits were habitual of human presence, unlike wild hares. When the hunting party arrived, the furries expected food from them after being kept locked in the cages for days. They were hungry, irritated, and angry. When the locks were open, instead of running for their lives, the rabbits raced towards the waiting congregation in complete retaliation.

Comments

Post a Comment